Conversion, Recovery and Relapse Prevention

By Jeff Jay

What do religious conversion and addiction recovery have in common?

Conversion is an awakening, and the formation of a new identity. It may begin dramatically, like the conversion of Saul, or it may develop haltingly over many years. In either case, it takes time, the help of other people and the grace of God to change Saul to Paul. In the process, there are times of great consolation and gratitude and times of desolation and darkness. As impatient as Paul could be with the Galatians, he was even more disappointed in himself. Yet Christ assured him: “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” (II Corin. 12:9)

Recovery is an awakening, and the formation of a new identity. It may begin dramatically, like the white-light experience of Bill Wilson, or it may develop haltingly with multiple relapses. In either case, it takes time, the help of others, and the grace of God to achieve contended sobriety. There are times of gratitude, and there are times of severe temptation. As impatient as we may get with people who relapse and cause other people pain, we are even more disappointed in ourselves when we cannot overcome our own defects of character.

What are the similarities between

Christian conversion and Twelve Step recovery?

Conversion is ultimately focused on the growth and salvation of the human soul. Its scope is at once intimate and eternal, boring into our innermost self, and stretching out beyond time. Conversion is rooted in our relationship with Jesus, and what he has done for us. Consider: infinite God becomes finite man, clears a path for us through His own suffering, death and resurrection and guides each one of us beyond the reach of evil and into eternal life. There is nothing which lies outside the bounds of this drama, and every individual human being is a critical character in the story. The transformation described by the word metanoia lies at the heart of conversion.

Recovery is focused on perhaps the most intractable problem of human life: addiction, a physical, psychological, and spiritual malady that compromises the will of the afflicted individual. Recovery is rooted in the here-and-now, in the fight against temptation, unnatural appetites and self-destruction. The process of moving from the isolation of a chronic illness into a community of survivors is the return route to health and balance.

Experience shows that recovery is “contingent on the maintenance of our spiritual condition,” even though the disorder is known to have a major genetic component, as well as co-occurring psychological factors. To be successful, one must rely on the grace of God, as expressed through other people and in the mysterious workings of the human heart.

Recovery is a form of conversion, and probably the most effective means yet developed to overcome what was once considered an intractable sin. The process is straightforward, but paradoxical in that the individual must admit defeat in order to regain control.

Conversion and recovery through surrender

When I was a hopeless alcoholic and drug addict living on the street, I didn’t believe recovery was possible. My downward spiral had accelerated to the point of no return, and I was seemingly beyond the help of family and friends. Fortunately, they prayed for me when I could not, and took action when I would not. I was an atheist in those days, forgoing even foxhole prayers. Suicide seemed like a reasonable option.

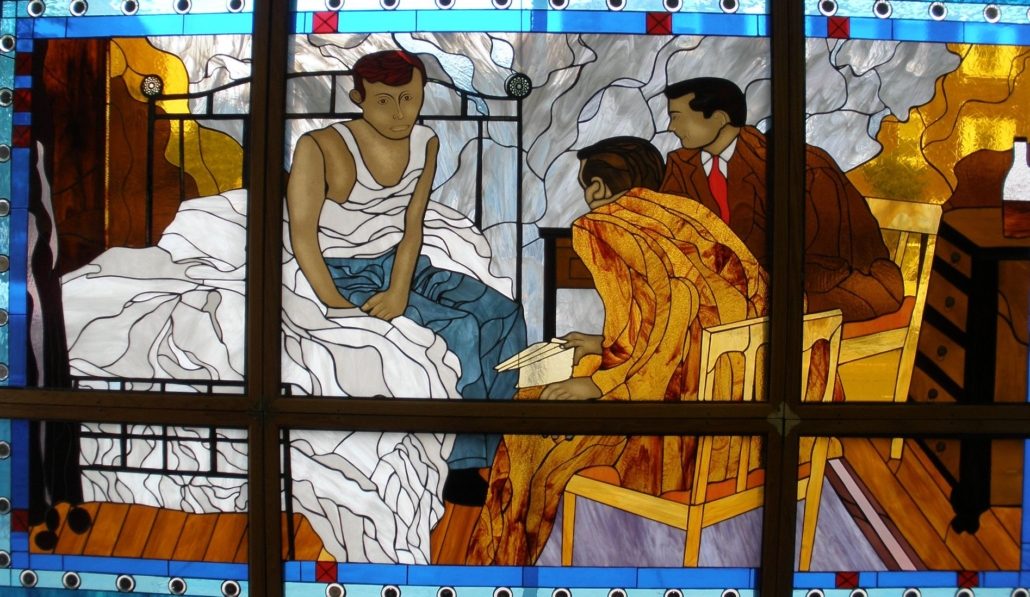

An unconventional intervention resulted in my being hospitalized, detoxed over a period of ten days, and then transferred into a month-long inpatient treatment program. The most prominent physical aspects of the disease were addressed in the detoxification process, and the psychological aspects of the illness were addressed during the many individual and group counseling sessions that followed. Still, my core belief system stood as a barrier to progress. I still wanted to be in control.

In this dark season of my life, I was the final authority on all issues. Of course, I had almost killed myself with alcohol and drugs, so the wisdom of my choices was suspect—even to me—but I dismissed the notion of God. I was determined to think my way out of the problem, yet I knew when it came to addiction my thinking was inherently untrustworthy. No matter how I tried to frame the issue, I seemed destined to fail. I was technically sober, but I had not overcome my alcoholism.

The conversion process from the hell of active addiction to the deliverance of active recovery embraces all the possible definitions of metanoia. In the language of the Twelve Steps, terms like sin, confession, repentance, and the like may be missing, but they are crystalized in the literature of the program very clearly. Indeed the Twelve Steps may be the most practical application of these principles in our current era.

There was no recovery for me until I surrendered. In that midnight hour of despair, I knew that I couldn’t contend with my demons alone, and that I was destined for failure, and probably death. I was overwhelmed with regret and hopelessness. Everything changed when I got down on my knees and cried out to God from the depth of my soul. In a moment outside time, the light burst through and annihilated the darkness, freeing me from the bondage of my illness. I was in the presence of Christ, and my new life was born in a rapture. I knew I could stay sober, because I was no longer relying on myself alone. I was overwhelmed with gratitude.

The word metanoia is rich with meaning. Jesus calls us to repent, change our minds, change our hearts, bear new fruit, be converted, live differently, come to believe, spread the good news, and more. Its implications are challenging, exhorting us to something we can immediately understand, yet never fully accomplish.

The word recovery is also pregnant with meaning. We get clean and sober, surrender to win, come to believe, clean house, make amends, and live our lives “happy, joyous and free.” It is not an event, but an ongoing process, and there is no graduation. It means much more than simply quitting our drug of choice or compulsive behavior. It is necessary to stop the behavior, but stopping by itself, without an active program of recovery, is a recipe for misery, and will likely lead to a relapse.

An addict who quits their addiction through will power alone is like the religious convert who uses will power alone to amend their behaviors. Where is God in the process? Where is grace? How can we move from the isolation of our defects and the shame of or sins to the “sunlight of the spirit” described in recovery literature or in the New Testament? There is a better alternative. “If we walk in the Light as He Himself is in the Light, we have fellowship with one another, and the blood of His son Jesus cleanses us from all sin.” (1 John 1:7)

The three-fold nature of addiction

Of course, there is more to addictive disorders than the spiritual dimension. I learned an important lesson about this as a young counselor, when I had the privilege of hearing the great Dan Anderson, Ph.D., give a lecture on the subject. He was president of Hazelden and a legendary psychologist. I remember his enthusiasm on the dais as he filled a large whiteboard with diagrams and bullet points. He emphasized the three-fold nature of addiction:

1. Physical

2. Psychological

3. Spiritual

“We can abstract any one of these for the purpose of study,” he said. “But we must always remember that the alcoholic does not experience them as separate. The alcoholic experiences alcoholism.”

He was subtly admonishing the researchers and theoreticians who were always trying to reduce the problem to one key element, in order to produce a unified theory. Dan’s point was holistic and complex, avoiding the temptation of over-simplification.

He went on to delineate the goals of treatment.

“One: to break through the patient’s denial at depth. Two: to get the patient to commit to a long term program of recovery.”

The first point is largely psychological, but the second point is spiritual. We alcoholics need the help of others on a long-term basis to remain sober and to be contented in our sobriety. There are not enough professionals in the world—nor the money to pay them—to rival the care provided free of charge by the community of recovering people.

In my work as an addiction counselor over thirty years, I’ve come to appreciate the spiritual component more and more. There has been tremendous work done on the physical aspects of addiction (genetic, epigenetic, neurobiological, etc.), and on the emotional and psychological aspects (understanding co-occurring disorders, trauma, attachment theory); but the spiritual component seems to be the glue that holds it all together. The reason is that, ultimately, the patient must manage their own recovery, and the spiritual component provides the most reliable fuel for that journey.

Addiction, like diabetes and many chronic illnesses, cannot be managed professionally. They can be medically monitored, and suggestions given, but hourly and daily management of the chronic condition must be done by the patient. If the patient is still playing God, which is the norm for a person suffering from a substance use disorder, their chances are slim until they can identify a new higher power.

There are various aspects to religious conversion, and how they unfold and express themselves over days, months, and years can be anything but straightforward. We might study the various elements of metanoia and conversion, but in some regard they are always just out of reach.

The most celebrated conversion story in the New Testament is the transformation of Saul to Paul. His encounter with Jesus isn’t preceded by repentance, nor is he seeking help. He believes he is acting righteously in the service of the God of Moses, and his pride is formidable. It’s no surprise that Jesus literally knocks him off his high horse.

Saul quickly comes to repent his persecution of Jesus’ followers, but he is not ready to take on the full persona of Paul, as we will come to know him in Acts and through his letters, for quite some time. His faith in Jesus is all but immediate (it could hardly be otherwise), but it takes time to gel, and he must begin under the tutelage of others, experiencing some false starts and time in the desert. He was not an overnight sensation with other Christians.

Most alcoholics don’t have a thunderbolt moment where everything changes and the power of God is revealed. Most change gradually, first coming to meetings, then thinking more clearly, and finally rekindling their faith.

The Twelve Steps: a recipe for recovery and conversion

The Twelve Steps offer a simple recipe for recovery—or conversion—that anyone can follow. Here is an overview of the process that leads to a change of heart that will “produce fruit in keeping with metanoia.” (Mt. 3:8)

Step One: “We admitted we were powerless over alcohol and that our lives had become unmanageable.”

This step is focused on humility, surrender, and acceptance. It’s difficult because all addicted people hope and believe they will somehow regain control of their addiction. We don’t want to give up our drug of choice, we want to reassert control and escape the consequences. It is magical thinking, and ultimately we collapse under the weight of despair.

Step Two: “Came to believe that a power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.”

Here we find simple advice on how to kindle a flicker of faith when there is none to be found. It does not ask for confession or profession; it barely asks for assent. Indeed the Step turns on the word “could.” It points addicted people toward the light, toward the merest possibility that there could be a power greater than ourselves that could deliver us from soul sickness.

Step Three: “Made a decision to turn our will and our life over to the care of God, as we understood Him.” (Italics in the original)

This is a real commitment, but with a loophole big enough to accommodate any faith or none at all. The third Step calls for an interior action which solidifies our commitment to sobriety. Many people bristle at the idea of turning their will over to someone or something else. But the Step asks us to turn it over to the care of God, to make our wills congruent with His. So with every significant action, the question becomes, “What would God have me do?”

Step Four: “Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.”

Step Five: “Admitted to God, ourselves and another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.”

The concepts of repentance and confession are developed in these steps. Most addicted people have tremendous difficulty in addressing these Steps thoroughly. Not surprisingly, a failure to do so often results in relapse. Most addicts take several weeks to write out their fourth step inventory, under the guidance of a sponsor. Great emphasis is placed on listing resentments and identifying their underlying causes. In many cases, the causes are found to be “selfishness and fear” — a good description of the human condition.

Step Six: “Became entirely ready to have God remove these defects of character.”

Step Seven: “Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.”

These steps also go together, and they constitute a big step forward in the spiritual life. Alcoholics Anonymous is clear in stating “We are not saints…we are only trying to grow along spiritual lines.” After completing Steps Four and Five, there are usually serious character defects which have been uncovered, and Six and Seven provide a method for addressing them. A method which assumes the grace of God, and its ability to work miracles in the human heart. We find that God will indeed remove these defects of character, but this miracle—and the ongoing miracle of recovery itself— is “contingent on the maintenance of our spiritual condition.”

Step Eight: “Made a list of all people we had harmed and became willing to make amends to them all.”

Step Nine: “Made direct amends wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others.”

Repentance means nothing without action, and in the case of addicted people that means making reparation for many years of wrongdoing. Steps Eight and Nine go together to help people right as many wrongs as possible. The program makes little distinction between faith and works. One of the favorite maxims of the early AA’s came from the Epistle of James: “Faith without works is dead.” (James 2:26)

Step Ten: “Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it.”

This step is sometimes referred to as a maintenance step, as it is done on a daily basis. It has some resemblance to the Ignatian Examen. The belief here is that honesty, humility, and action will protect us from backsliding. Real conversion is an ongoing process, and Step Ten is a compact commandment for staying on course.

Step Eleven: “Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God, as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of his will for us and the power to carry that out.”

The Step presupposes a number of things: 1) we need to improve our conscious contact with God, 2) that God is accessible through prayer and meditation, 3) that He will guide us, 4) that He will provide the power to do what needs to be done. We are always falling short, and God will always lift us back up again. If we will let him. Usually through the agency of other people.

Step Twelve: “Having had a spiritual awakening as a result of these Steps, we tried to carry this message to other alcoholics and to practice these principles in all our affairs.”

Step Twelve introduces the essential element of the Steps: the concept of service to others. This is not mere altruism, but the sine qua non of recovery. For the early AAs, the admonition of St. James said it all: “Faith without works is dead.” After his profound spiritual awakening, Bill Wilson, co-founder of AA, discovered that he had to work actively with other alcoholics in order to maintain his own sobriety. Carrying the message was a necessary part of the recovery process. It made no difference whether the prospect stayed sober or not, the act of selfless service was critical to his sobriety.

Dr. Bob Smith, the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, talked about the reason he had not been able to stay sober until he met Bill. Dr. Bob had been praying for deliverance, and he was also attending Oxford Group meetings in Akron, Ohio as Bill had done in New York. However, Dr. Bob stated: Bill had “acquired the idea of service. I had not.” Carrying the message to other alcoholics helped Dr. Bob stay sober, and millions of other people after him. “You have to give it away to keep it.”

Yet people can and do relapse; and here the experience of recovery and religion come even closer.

Overcoming and Preventing relapse

Years ago, when I was working as a counselor in an inpatient treatment center, one of my responsibilities was running a Relapse Prevention group for recidivist patients. Most of the men blamed their relapses on external factors: job pressures, break-ups, financial problems, an unexpected death, and so on. However, these are normal hardships in life, and they do not cause relapse in most people. What was the core issue? In most cases, it was a spiritual matter.

Most of the men followed a familiar pattern on the way to relapse, whether the process took days or weeks to culminate in a drink. After having been sober for some period of time, they had: 1) cut down on their Twelve Step meetings, 2) spent less time talking to their sponsor, 3) stopped going to meetings, 4) stopped talking with any group members, 5) relapsed.

Yet underneath these externals was a more relevant spiritual factor. When I asked them about their prayer life, a great commonality emerged. While they were in active recovery, some had prayed to the God of their understanding, some prayed haphazardly in tandem with the literature of recovery, some prayed only at the beginning or end of Twelve Step meetings, along with the other group members (typically the Serenity Prayer at the beginning and the Lord’s Prayer at the end). All had begun to have at least a semblance of a spiritual practice. But before their relapse process began, the spiritual spark had begun to fade. They had relaxed their spiritual discipline, and this had preceded the relapse.

Yet it is too simplistic to say that prayer alone governed their sobriety or relapse. The Twelve Steps are a program of faith in action, with the emphasis on action. Prayer and religious practices by themselves were tried for many centuries as an antidote for addiction, but with scant success. What was missing?

The combination of faith and works. Real metanoia should result in a change so profound it can be seen by others. How better to see it than in selfless service to others?

Besides a cooling off in the spiritual life, there is a well-known path by which addiction reasserts itself in the mind of the addict. Perhaps the most concise description of mental relapse was written six hundred years ago by Thomas à Kempis in The Imitation of Christ. Though he was writing about temptation and sin, his explanation is still clinically astute.

“This is how temptation is: first we have a thought, followed by strong imaginings, then the pleasure and evil emotions, and finally consent. This is how the enemy gains full admittance, because he was not resisted at the outset.” The Imitation of Christ, Book 1, Ch. 13

“First we have a thought….” We welcome it in, make it feel comfortable, and spend time with it. To coin a phrase: we entertain the thought.

“…followed by strong imaginings….” We are now in league with the temptation, actively increasing its allure. The danger is escalating, and because our prayer life has cooled, we are less likely to call out for help, either to God or to our friends. We are left to our own devices, and the old isolation.

“…then the pleasure and the evil emotions….” We are now enjoying the seduction, magnifying its power, and succumbing to the fantasy we are entertaining. We are powerless to resist, though we know the consequences may be dire. We are enthralled by the prospect.

“…and finally consent.”

In the same chapter, Thomas also gives an exquisite solution to temptation, which parallels the value of Twelve Step groups. His brilliant and compact prose lifts the spirit.

“When you are tempted, seek the advice of a wise counselor, and do not yourself be harsh with persons who are tempted; rather be happy to console them as you yourself would wish to be consoled.”

Where better to find a wise counselor than the local Twelve Step meeting? Where better to find someone who might need to be consoled? Where better to find the opportunity for service and support? We recovering people keep going to meetings for many reasons, but most often it is simply to give and receive the kindness that was given to us from the outset. We also find that our greatest defect and liability has become our greatest asset and qualification, because we can share our experience, strength and hope with the newcomer.

I have often seen the eyes of a shaky subject light up as they recognized a fellow traveler. I have been privileged to see the rebirth of hope and the slow, steady development of faith. Interestingly, twelve-steppers have figured out how to do this without hewing to one religious tradition or another. I have personally witnessed meetings attended by Christians, Jews, Muslims, and agnostics without any acrimony passing between them. The grace of God is sufficient.

There is a powerful connection between addiction recovery and religious conversion. The parallels between the basic texts of Twelve Step literature, on the one hand, and the Scriptures and spiritual masterpieces of our traditions, on the other, are everywhere. The recovery movement is a direct offspring of Christian conversion, putting faith in action to overcome addiction.

Jeff Jay

Jeff Jay